The founder of Rome, hidden inside a metaphor

Every now and then, I’ll obsess about something and I’ll try to learn absolutely everything I can about a minuscule part of our history or knowledge. This is how I learned about the most important prostitute in history.

The foundation of Rome is a historical mystery surrounded in metaphors, legends, and mythology. So much so that Ancient Roman historians narrate these events as legends. The most accepted tale begins with Aeneas sailing the Mediterranean to what today is Italy, after it was foretold that in Italy “he will give rise to a race both noble and courageous”, as Virgil narrates in the Aeneid. Virgil’s work, one of the most notable poetic works in Latin, focuses primarily on Aeneas’ adventures, similar to a Homeric epic, and his resettling of the Trojan people after the war.

We will have to skip a few hundred years, since the Trojan War is believed to have happened 1260–1180 BC.

Titus Livius (Livy), probably the most renowned Roman historian, narrates in his only surviving work, Ab Urbe Condita (approx. 30 BC), that the foundation of Rome begins about 500 years after the time of Aeneas, when Numitor, descendent of Aeneas and King of Alba Longa, is overthrown by his brother Amulius. In an effort to make sure there aren’t any future claims to the throne, Amulius kills Numitor’s two sons and makes his daughter, Rhea Silvia, a Virgin Vestal. Failure to stay virgin would be punished with torture and death, meaning Rhea Silvia would never give birth to any competitors to the throne.

Big mistake. Livy writes:

The Vestal was ravished, and having given birth to twin sons, named Mars as the father of her doubtful offspring, whether actually so believing, or because it seemed less wrong if a god were the author of her fault.

Those twins were Remus and Romulus, today considered the founders of Rome. As Livy mentions, it was speculated that Mars was the father of the twins. It’s likely that Rhea Silvia and others suggested Mars as the father so that Amulius wouldn’t dare to enrage the god by killing either the mother or the twins.

Amulius, then, decided that if the twins weren’t killed by his own sword, they would not be punished. He instructed the twins to be thrown to the river Tiber. Fortunately for them, the river had overflowed and Amulius’ men decided to just drop the kids by the backwaters of the river, thinking they would be enough to drown them.

This is where the true legend begins. Livy writes:

(…) a she-wolf, coming down out of the surrounding hills to slake her thirst, turned her steps towards the cry of the infants, and with her teats gave them suck so gently (…)

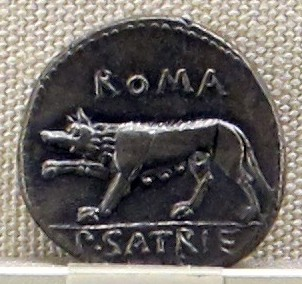

Ah, yes. The mighty she-wolf. This she-wolf:

You might’ve heard the legend of the she-wolf who briefly nurtured the twins, until they were found by Faustulus, a shepherd. Even Roman historians understood this story as a metaphor. Livy writes:

Tradition assigns to this man the name of Faustulus, and adds that he carried the twins to his hut and gave them to his wife Larentia to rear. Some think that Larentia, having been free with her favours, had got the name of “she-wolf” among the shepherds, and that this gave rise to this marvellous story.

This is where my curiosity begins. Having read Livy in Spanish before reading it in English, I noticed something was off. Most English-speaking history writers and bloggers consider the fact that Larentia was nicknamed a she-wolf something unique or amusing, but this is lost in translation. Even Benjamin Oliver Foster’s translation, from 1919, which I’ve used in this post, adds a footnote to the paragraph above that reads:

The word lupa was sometimes used in the sense of “courtesan.”

Spanish is my first language and, to me, this is not news. To this day, in Spanish we still use the word loba to describe a woman “free with her favours”, as Livy defines so succinctly, or to describe a woman who is sensual. Not only that, but the word lupanar, coming from the same root lupus — wolf, means brothel in Latin, French, Portuguese, and Spanish today .

Faustulus’ wife, Larentia, is the main character of this post and, in my opinion, one of the most important prostitutes in history. Livy, as a historian in the late Roman Empire, knew the fable of the she-wolf was too good to be true and understood the cultural significance of calling a woman a “she-wolf”. In fact, the Latin version of the same paragraph has more subtlety that English translations have failed to grasp:

sunt qui Larentiam vulgato corpore lupam inter pastores vocatam putent: inde locum fabulae ac miraculo datum

is translated by Benjamin Oliver Foster as:

Larentia, having been free with her favours, had got the name of “she-wolf” among the shepherds, and that this gave rise to this marvellous story

However, in the context of Livy, Latin culture, and subtle syntax, I believe that’s not an accurate translation. I would translate it more as:

There are those who think Larentia shared her body around, so shepherds called her a prostitute.

Because you see, in that context, lupam shouldn’t even be translated as “she-wolf” but directly as “prostitute”. In fact, many translations to Spanish skip the explanation step of the sentence and simply state that she shared her body around, so that was the origin of the story.

We stop the history lesson here and try to answer the main question of the post.

Who was Acca Larentia?

Larentia would later be known as a goddess, and deified by Romans. Initially celebrated only once a year, in the Larentalia, Augustus eventually ordered the Romans to celebrate her twice a year.

If we ignore the deified aspect of Larentia, we can find some interesting primary sources (or as primary as we can find, given that this happened around 700 BC), that describe her in more detail.

Aulus Gellius, born in 125 AD in Rome, writes at length about Larentia in Attic Nights, his only surviving work. Attic Nights is a compendium of notes, the closest to a Tumblr for that time, and small excerpts he wrote on grammar, philosophy, history, and others. Gellius writes:

But Acca Larentia was a public prostitute and by that trade had earned a great deal of money. In her will she made king Romulus heir to her property, according to Antias’ History; according to some others, the Roman people. Because of that favour public sacrifice was offered to her by the priest of Quirinus and a day was consecrated to her memory in the Calendar. But Masurius Sabinus, in the first book of his Memorialia, following certain historians, asserts that Acca Larentia was Romulus’ nurse. His words are: “This woman, who had twelve sons, lost one of them by death. In his place Romulus gave himself to Acca as a son, and called himself and her other sons ‘ Arval Brethren.’ Since that time there has always been a college of Arval Brethren, twelve in number, and the insignia of the priesthood are a garland of wheat ears and white fillets.”

By the time Gellius wrote this, the Roman Empire was nearing the end of polytheism, slowly devolving into self-appointed deity statuses and politicians attempting to convert emperors into gods. (Senators even attempted to name Emperor Augustus a god, but he declined believing he was the son of a god, but not a god himself).

So far, from Gellius’ account, we see a slightly different depiction of Acca Larentia. It’s very likely that after losing her newborn at birth, she adopted Remus and Romulus as her own. Unfortunately, the Antias’ History that Gellius mentions was lost forever.

There’s a far more mythical depiction of Acca Larentia, which is that of a young woman given to Heracles as part of a bet. He told her to try and seduce the first wealthy man she saw, eventually marrying him, inheriting his fortune, and then bequeathing it to the people of Rome.

Plutarch, Greek essayist (AD 46 — AD 120) explained this in his work Romulus:

(…) Larentia, who was then in the bloom of her beauty, but not yet famous, he feasted her in the temple, where he had spread a couch, and after the supper locked her in, assured of course that the god would take possession of her. And verily it is said that the god did visit the woman, and bade her go early in the morning to the forum, salute the first man who met her, and make him her friend. She was met, accordingly, by one of the citizens who was well on in years and possessed of considerable property, but childless, and unmarried all his life, by name Tarrutius. This man took Larentia to his bed and loved her well, and at his death left her heir to many and fair possessions, most of which she bequeathed to the people.

Plutarch’s point of view is useful. Initially Greek, later obtaining Roman citizenship, he has an outside point of view that allows us to understand the origin of this legend. In the same book, he writes a bit before:

But some say that the name of the children’s nurse, by its ambiguity, deflected the story into the realm of the fabulous. For the Latins not only called she-wolves ‘lupae,’ but also women of loose character, and such a woman was the wife of Faustulus, the foster-father of the infants, Acca Larentia by name.

There was no wolf. Just Larentia

Prostitute or not, Larentia was likely a powerful woman, and most primary sources seem to indicate she supported Remus and Romulus in their task of taking back the throne from Amulius and founding Rome. It is also very likely that she supported economically the very first steps of a culture that lasted hundreds of years and shaped western culture forever.

It’s not the first time that a powerful woman is hidden, purposefully or not, by metaphors or trivialized by calling her a prostitute.

I’m not a historian or a good, reputable source on history. If you see anything amiss, let me know.

Sources (and recommended reading):

- Atticus Nights, by Aulus Gellius. (Translation by John C. Rolfe). http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2007.01.0072%3Abook%3D7%3Achapter%3D7#note-link2

- Romulus, by Plutarch.(Translation by Bernadotte Perrin)

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:2008.01.0061:chapter=4&highlight=larentia - The History of Rome, Book 1 by Titus Livius (Livy) (I used translations by Rev. Canon Roberts and Benjamin Oliver Foster)

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0151%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3D4 - Aeneid, by Virgil. (Translation by P. Vergilius Maro) http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0054%3Abook%3D1%3Acard%3D1